Moss is the simplest and most rudimentary of all land plants. Yet its importance in the ecological world cannot be understated.

Did you know that there are over 22,000 types of moss? They are intricate and beautiful, and essential to our ecological world. Let’s discover how critical they are.

With a loupe, also known as a geology lens, you can really see the variations, colors, and textures of these fuzzy plants. Mosses vary greatly. Some have fronds like miniature ferns, while others have wefts like ostrich plumes or shining tufts like the silky hair of a baby. Certain varieties have leaves with large coarse teeth, some have a saw blade edge, or delicate fringe, or accordion pleats. Like interlocking puzzle pieces in varying shades of green, moss varieties can intermingle and cohabitate, weaving through and draping over snags, decaying logs, and rocks.

Each type of moss has its own scientific name. But the most common are sphagnum, which grows in bogs, and peat, which is compressed sphagnum moss.

Here are some interesting facts about these non-vascular plants:

- Mosses lack flowers, fruits, and seeds and have no roots.

- They have no vascular system, which does not allow the xylem to carry water and nutrients from the roots to the leaves or phloem, transporting food from photosynthesis to the rest of the plant.

- Moss thrive in the shade. They flourish in humid, moist zones where photosynthesis can occur.

- A thin layer of water over the one-cell thick leaf is how carbon dioxide enters the plant, transforming light and air into sugar.

There is a lot of life in one gram of moss.

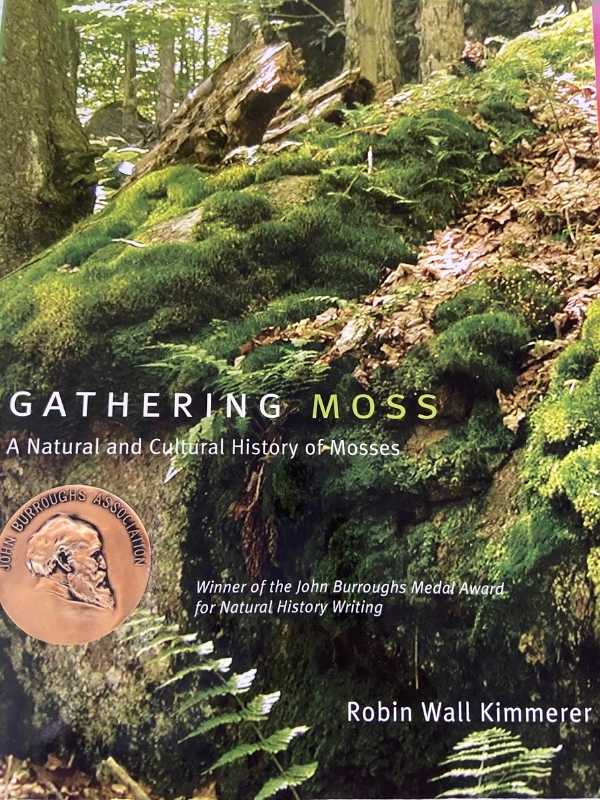

According to Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer: “the quality of life in one gram of moss from the forest floor, approximately the size of a muffin, would harbor 150,000 protozoa, 132,000 tardigrades, 3000 springtails, 800 rotifers, 500 nematodes, and 200 fly larvae.” That is a lot of life in just one gram (approximately 1/4 teaspoon) of moss! Kimmerer is the author of Gathering Moss, which is a mix of science, personal and teaching experiences, and Native American heritage. It’s a fascinating book that we highly recommend!

When these furry little plants reproduce, only half of the parents’ successful genes are passed to the offspring, and those genes are shuffled in the lottery of sexual reproduction. Most mosses can clone themselves from broken-off leaves or other torn fragments.

Traditional Native American knowledge is rooted in intimacy with the local landscape. The land is the teacher. We can learn a plant’s particular gift by being sensitive to where it comes and goes.

Here are some interesting facts that Dr. Kimmerer brings to our attention in Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses:

- Contrary to popular belief, mosses cannot kill lawn grass. They provide benefits like nutrient cycling to soil and other plants. They’re actually the perfect moisture-enriched nurseries for trees, ferns, seeds, fungi, slugs, and bugs.

- Mosses are exceptional at ecological restoration. They remove toxins from water and bind toxins to cell walls. Scientists are currently exploring whether these plants can assist with wastewater treatment and the protection of urban streams.

- These tiny plants are much more sensitive to air pollution damage than higher plants, making them useful as biological contamination monitors.

- There is no scientific evidence that supports or refutes the claim that mosses lead to shingle degradation and leaky roofs. In fact, moss can help protect cracking and curling roof shingles exposed to intense sun. It actually adds a cooling layer in the summer and slows stormwater runoff when the rains come.

- Moss pickers harvest from the forest, cram it into burlap bags, and cash their bundles in to florists to line flower baskets and create designer moss sheets. Unfortunately, harvested moss takes years to regrow, if ever.

- Moss eradication in the northwestern part of the U.S. is big business. Chemicals sold in hardware stores are harmful to the environment, ending up in streams and threatening salmon’s food chain.

As Dr. Kimmerer points out, moss also had many helpful and fascinating historical uses.

- Mosses were widely used as everyday tools by women for diapers, sanitary napkins, and insulation from the cold. Indigenous women often lined bags with moss to keep their children warm.

- During World War 1, when cotton supplies were limited by warfare in Egypt, sterile Sphagnum became the most widely used wound dressing in military hospitals.

- Peat has a long history of human use, ranging from therapeutic baths in ancient Greece to ethanol generation today. Burning bricks of dry peat was a vital heating source in colder northern climates.

- The smoke from slowly-smoldering peat permeating malted grains gives scotch whiskey its rich autumn taste. Peatlands are drained worldwide and used as a soil additive to grow certain specialty vegetable crops such as lettuce and onions.

- Birds weave soft, pliable mosses into their nests to cushion the eggs and provide an insulating layer. Bears, flying squirrels, voles, chipmunks, and many other animals line their burrows with bryophytes.

So, using your loupe, really take a good look at the moss you find on your next outdoor wilderness or forest adventure. What is happening in that tiny microscopic ecosystem?

You can also hear more about the fascinating world of moss and Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer on Dr. Jane Goodall’s Hopecast and Alie Ward’s Ologies podcasts.

You may also be interested in these blogs from One Planet Life:

Written by Yvonne Dwyer

Master Naturalist and OPL Content Contributor

“It is truly an honor for me to be a contributor to One Planet Life. By sharing my experiences and lifetime of learning, I hope to inspire conservation, sustainability, stewardship, and awareness of enjoying the natural wonders of the world for the wellbeing of people and the planet.”